Daring, unusual, innovative, and alluring, good design is far-reaching and astute in rigorous sensuality with a plethora of notable products by a variety of prolific and thought-provoking designers, all of whom have engulfed the design scene with thousands of works that transform our daily rituals and present new ways of perceiving our world with wonder and sublime freedom, noble and transcendent. When we look at the creative processes that gave life to many marvels of modern and contemporary design, we can’t help but wonder at where it all began, and how the development of life-changing products all stemmed from a journey of experimentation, with award-winning triumphs and awkward failures felt along the way, each design built on the lessons learned from the ones that came before it, meticulously refined and embracing of the risks and untried possibilities that address our desires and needs in ways we hadn’t previously imagined. When assessing the body of work produced by a celebrated and time-honored designer, it is fascinating to consider the origins of their work and unearth the potential that meandered through their very first designs, some investigational and unorthodox, others unleashing novel perspectives in the standard and established, yet all finding voice at the start of a voyage that would bring a refreshing verve to a landscape defined by the innovative and the unique, the rousing and the serene. It is in these initial designs that we uncover a creativity both insightful and tentative and learn that all virtuosity must get its start somewhere, however uncoordinated or clever, polished or raw, steeped in cunning imagination and resourceful ingenuity.

From esteemed prize-winning designs to novel experiments in material and form, the first designs of notable designers vary in maturation and scope, as does the social context in which they were created. Some, like Le Corbusier’s Villa Fallet, a family home built in 1907 above La Chaux de Fonds in France by a 19-year old Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, before he became Le Corbusier, diverged from the flat roof, glass intensive designs for which he later became known, opting instead for a pitched hip roof and an elaborately decorated villa in the style of Swiss chalets and Art Noveau. His wooden table, chairs, and built-in sideboard for the home similarly took on a distinctive “style sapin”, or fir tree style, reflecting the folage and motifs of its surroundings, hinting at a love for the simple and refined that crept into his later styles yet decisively influenced by collaborator and mentor Charles L’Éplattenier, a teacher at the school where Le Corbusier studied. While the style of the Villa Fallet did not necessarily become emblematic of Le Corbusier’s home as a machine for living, his first work bears the signature of sophisticated lines and cleanliness of form, a first in poised structure and continuity in theme, characteristic of its time yet celebrated still today as a treasure in wood and stucco.

While some firsts bore scant resemblance to the renowned styles of their maker, others embodied the very ethos and vision of all works that proceeded them, as with Naoto Fukasawa, whose very first pieces were conceived decisively from his “Without Thought” philosophy, a design approach that peers into one’s unconscious behavior, taking notice of how individuals act in their everyday and revealing solutions in these performances that bond the design to the person who uses it. Ever since his first piece for Muji, a wall mounted CD player that become an iconic design inspired by the intuitive ventallation of fans that activate once a cord is pulled, Fukasawa has taught this philosophy in workshops and crafted numerous pieces for Muji and other brands where he describes design as “attributing countenance to an object,” in which instinctual and well-crafted design lies in harmony with its environment and context. Other firsts similarly captured the spirit and personality of the designer, solidifying the foundation from which other works would follow, as with Philippe Starck's foray into living spaces as a young student at the Ecole Nissim de Camondo in Paris, where in 1969 he designed an inflatable structure based on the notion of materiality and the ephemeral, and reflecting the bold deviation from convention and rebellious spirit that characterized his career. Seduced by this iconoclastic design, Pierre Cardin offered Starck the position of artistic director at his publishing house, launching the career of the provocateur and enabling the manifestation of several emblematic and eccentric objects, including a floating lamp and portable neon sign, and sparking the start of his mission to channel design to improve as many lives as possible, merging the political with the poetic, the pragmatic with the subversive, the rational with the compassionate.

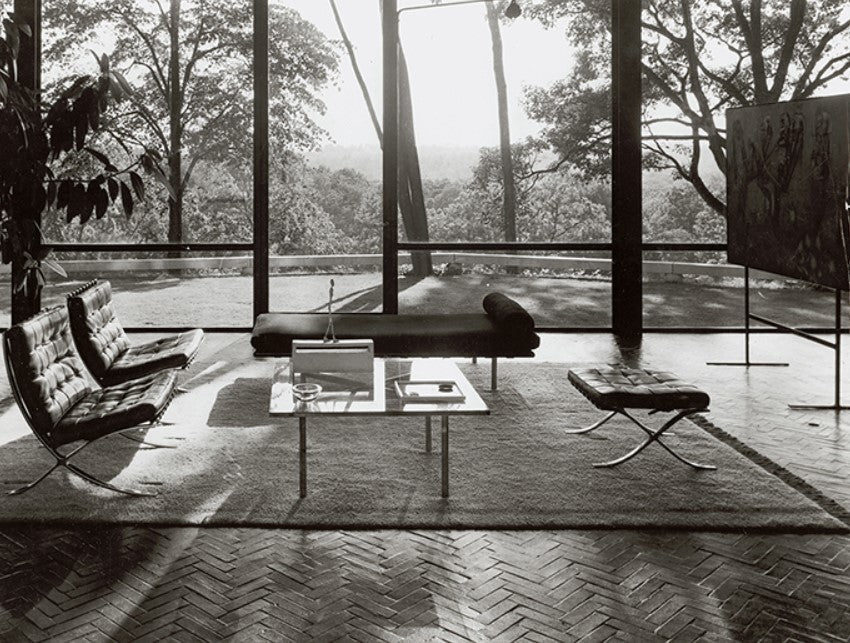

In a field where collaboration and mentorship helps guide young designers through a terrain at once complex and competitive, it is unsurprising that some firsts rose in partnership with other designers and colleagues, some while working as assistants to celebrated designers, as a young Patricia Urquiola alongside Vico Magistretti at De Padova, where she designed Loom, a three-seater sofa characterized by curvilinear designs of armrest and backrests, to cradle the body in comfort, and Flower, a small armchair whose delicate, organic form foretold of the fluid and feminine works she would later design in her own studio. Other collaborations came in the form of like minds working together to develop something new and pioneering, as when Eero Saarinen teamed up with Charles Eames for his first piece in 1940, the Organic chair, a small yet comfortable reading seat that received first place in the “Organic Design for Home Furnishings” competition organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Ahead of its time, it was not possible to mass produce organically shaped seat shells when the design was presented, but it opened the door for future products to be conceived, and when it became possible for such designs to be crafted in large quantities, the groundwork for Eames’ notorious Plastic Armchair and Saarinen’s renown Tulip chair had been set, ushering in a era of ergonomic, flowing forms that defined the mid-century modern and remains to this day admired for its grace and utility.

Some design firsts burst into the scene with notoriety and feted accolades, as with Zaha Hadid first built work for the Vitra Museum Campus, the Vitra Fire Station, whose sharply angled planes resembles a bird in flight, or Piero Lissoni's structured yet sublime collection for the kitchen, Esprit for Boffi, which earned a Compasso d’Oro and established his reputation as a designer worthy of acclaim with acute sensitivity to transformative aesthetics. Others embarked on the world with a quieter aplomb yet spoke to a rare ingenuity as with Achille Castiglioni's Leonardo table for Zanotta, whose sawhorse legs evoked the power of common objects to elevate the unconventional, or Konstantin Grcic’s Refolo office trolley for Aleph Atlantide, a modular system whose pared-down design and bold use of color speaks to his “take it easy” approach, where the best design is work that is simple and functional. Whether experimental or tried and true, renowned and illustrious or discreet and unassuming, the first products crafted by these distinguished designers are remarkable in their initiative and stalwart in their vision, immersed in a history and tradition of investigation, curiosity, and discovery, telling the stories of a human-centered approach to design with a prophetic glimpse into what was yet to come, courageous, charismatic, and unique.

May 2024